LAURIE VANHOOSE | TREATY OAK STRATEGIES

The Accountable Health Communities (AHC) Model was a 5-year Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Innovation Center project (running May 2017 to April 2022) that tested whether systematically identifying and addressing the health-related social needs of Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries’ through screening, referral, and community navigation services has an impact on healthcare utilization, including emergency department visits; inpatient admissions, readmissions, and utilization of outpatient services; total cost of care; and/or the provider and beneficiary experience.

Three hospital systems in the Houston area (Harris Health, Memorial Hermann, UTHealth Houston/Houston Physicians) were awarded an AHC Model grant from CMS and expressed interest in engaging Medicaid Managed Care Organizations (MCOs) to discuss opportunities to continue the work implemented via the CMS grant.

In September of 2022, the Episcopal Health Foundation contracted with Treaty Oak Strategies (TOS) to convene the AHC-Houston site partners to discuss alternative payment models (APMs) and other opportunities to sustain the model using the Medicaid managed care program in Texas.

Background

CMS awarded AHC Model grants to bridge organizations to serve as “hubs”. These bridge organizations were responsible for coordinating AHC efforts to:

- Identify and partner with clinical delivery sites,

- Conduct systematic health-related social needs screenings and make referrals, and

- Coordinate and connect community-dwelling beneficiaries who screen positive for certain unmet health-related social needs (HRSNs) to community service providers that might be able to address those needs.

The AHC Model screens for five core HRSNs:

- 1. Housing instability: homelessness, poor housing quality, inability to pay mortgage/rent

- 2. Food insecurity: difficulty paying for enough food

- 3. Transportation problems: transportation needs beyond medical transportation

- 4. Utility difficulties: difficulty paying utility bills

- 5. Interpersonal violence/safety: intimate partner violence, elder abuse, child maltreatment

The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth) School of Public Health served as the bridge organization for the Greater Houston AHC (GH-AHC) Model which includes 13 clinic delivery sites (CDSs) across the three large health systems. The CDSs included four ambulatory clinics, five hospital-based EDs, and four hospital labor and delivery departments in the Greater Houston area.

All community-dwelling Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries, including those dually enrolled, seeking care from one of the 13 CDSs were eligible for screening. Beneficiaries were eligible to be screened up to and including five business days before their scheduled ambulatory clinic appointment and up to and including five business days after their visit to the hospital ED. Labor and delivery beneficiaries were eligible to be screened during their hospital stay. Eligible beneficiaries were screened using the 10-item AHC screening tool. All model participants were required to screen individuals using the AHC HRSN Screening Tool. As of June 2022, more than 1.1 million unique patients had been screened within the model.

The model requires at least monthly outreach from navigators to patients to learn more about their HRSN(s) and identify barriers to resolving them and progress toward a person-centered action plan to connect with community services to resolve their needs. The eligibility criteria for navigation services are at least one HRSN and self-report of 2 or more ED visits in the prior 12 months. As of June 2022, more than 137,000 patients accepted navigator help connecting to resources for their HRSN(s), which is a higher level of acceptance than anticipated (more than 80% of those eligible), and patients reported that over 92,000 of their HRSNs were resolved through the model. An initial evaluation report released in 2020 found that nearly 60% of patients eligible for navigation had 2 or more HRSNs.

The initial findings from the GH-AHC Model were included in an article published in the American Journal of Accountable Care in December 2020:

APM Planning Project: Key Lessons Learned and Observations

Infrastructure

The GH-AHC Model involved multiple health systems with the UTHealth School of Public Health serving as a bridge organization. One of the key elements that made the initial model successful was the infrastructure that was implemented to administer the project: data sharing, automation, and practice workflows. The bridge organization was also fundamental in ensuring referrals, navigation, tracking, and data collection.

The initial evaluation of the AHC Model found that screening was not typically integrated in existing clinical processes, but instead was implemented as an add-on to workflow. Many of the AHC Model sites hired new staff to manage screening and referral processes; clinicians were not always aware of screening results either because the practice’s electronic health record system did not integrate results or because clinicians did not review the information. Some care management teams did not engage physicians in AHC screening, referrals, or navigation to avoid adding to their workload.

The GH-AHC sites implemented a very structured processes by automating and building processes and infrastructure around existing workflows. This automation allowed for real-time data feeds from partners as individuals were discharged from the ED, were admitted to labor/delivery departments, or visited an ambulatory setting. Screening automation allowed identification of high-risk individuals during their visits, which then initiated a screening, allowing determination of HSRNs and automatic generation and printing or emailing of referrals to the individual.

Data sharing between clinical and community partners is a critical component of the AHC Model. Effective data sharing streamlines referrals, improves care coordination, reduces screening fatigue, and impacts practice workflows. The automated nature and the infrastructure built into the design of Houston’s model is what makes it an appealing model and a great partnership for an MCO. It also allows for easy generation of reports. The GH-AHC partners stressed the importance of an APM recognizing the initial investment to implement necessary infrastructure.

The biggest hurdles to overcome for providers and MCOs when implementing an APM is the ability to automate processes and share data in a timely manner, as a key issue MCOs struggle with is accessing timely information about ED visits, hospital admissions and discharges, and member information necessary to coordinate care and ensure appropriate interventions to impact health outcomes. These concerns are important to continue leveraging during any further MCO discussions and APM negotiations and were the primary points of interest MCOs expressed during discussions.

The UTHealth School of Public Health serving as the bridge organization provided the backbone of the GH-AHC Model’s infrastructure. However, they are not a provider of services making it difficult to negotiate an APM directly with an MCO, and three-party APMs are very complex and difficult to implement. Excluding the bridge makes it initially very difficult and administratively burdensome for health systems to utilize the model. The health systems indicated that starting with infrastructure grants from MCOs would be beneficial to help health systems build out the necessary automation and workflows. Infrastructure grants could also help make the model sustainable long-term for a health system.

Screening

GH-AHC implemented a 90-day restriction around re-screening individuals seen at various locations. This was important to prevent screening fatigue, which is an issue of discussion between providers, community-based organizations (CBOs), MCOs, and HHSC today. GH-AHC sites’ experience with this rule provides an opportunity to learn from if the MCOs and HHSC wish to take screening fatigue into consideration as Service Coordination and NMDOH screening requirements continue to evolve.

GH-AHC Model sites gave critical observations of the screening tool. Since this is not a tool designed for or specific to Texas, they noted that some of the questions appear biased to other parts of the country – specifically the transportation questions. Texas recently passed HB 1575, which requires HHSC to streamline NMDOH screening questions across MCOs. If an APM, there may be the need to streamline screening questions used by the health systems with the new MCO screening questions.

APM Negotiation and Administration

Unlike what has been shared in other conversations by providers, the health system contracting and administrative staff expressed concerns around APM negotiation with the MCOs and the ongoing administration of the program. The entities that manage MCO contracts for the health systems expressed concern that while the individuals that were designing the APM had great ideas and the model could provide great benefit to individuals in Houston, the contracting would be extremely cumbersome, and the ongoing administration and reporting may not be feasible. Any future discussions should include contracting and key health system staff from the beginning, and building trust with MCOs will be necessary to advance any future APMs. Additionally, it will be important for leadership to invest in and prioritize APM negotiations and implementation of the program so that staff understand the importance of finding solutions to barriers that hinder implementation.

MCO Procurements

During the APM discussions there was some instability in the Medicaid program due to STAR+PLUS and STAR/CHIP requests for proposals (RFPs). HHSC was reprocuring the RFPs during this EHF planning project. Given the GH-AHC project’s focus on Medicaid- and Medicare-eligible populations, TOS initially recommended that the project sites focus on STAR+PLUS and STAR populations for initial conversations with MCOs. Timing ended up being an issue; HHSC announced STAR+PLUS contract awards in February 2023 resulting in changes in MCOs in the service delivery area (SDA). The MCOs were also very busy with the STAR and CHIP RFP responses during the summer and fall of 2023.

The Medicaid program should be more stable in the fall of 2024, which may be a good time to reinitiate conversations because STAR+PLUS will be live and MCOs will know if they won their STAR and CHIP bids and in which SDAs they will have contracts in the future. This knowledge will make APM discussions more concrete and will give MCOs greater confidence in investing in and partnering with providers.

CBO Capacity

It will be important to continue considering the capacity of area CBOs. Nationally, the AHC Model Bridge organizations noted that CBOs often have limited capacity and funding to support their work and that increased client volume does not equate to additional resources. One bridge organization noted that getting CBO buy-in for data-sharing initiatives is a major challenge because most of the funding to implement these systems is going to providers and not to CBOs. Increased workloads and limited funding can discourage CBOs from participating in data-sharing initiatives and in these types of partnerships. If the GH-AHC sites are screening for HRSNs but CBOs lack capacity for referrals, we will not see the desired outcomes.

Engage MCOs Earlier

APM Design and Quality Metrics

Quality Metrics

Through the MCO contract and via several quality programs (Pay for Quality, Value Based Enrollment Incentive Program, and MCO Report Cards), Texas MCOs are held accountable to the same metrics the AHC Model aims to impact: decreased ED visits, inpatient admissions, and readmissions; decreased total cost of care; and the provider and beneficiary experience. HHSC is implementing APM requirements for MCOs to support system-wide change. Since the AHC Model goals and MCO quality metrics are aligned, there is greater incentive for MCOs to enter APMs to sustain the AHC Model.

Data

Per the discussion above, data is instrumental in the success of the AHC model but is also a key element of APM development, negotiations, and on-going reporting. In several conversations, subject matter experts in the hospital systems expressed concerns about being able to pull the right data and get necessary data from MCOs. Many different types of providers continue to express frustration that they do not have a full picture of clients and need data from MCOs to develop an APM and negotiate appropriate benchmarks. Our discussions around the GH-AHC model and APMs were no different. Future conversations will need to identify necessary MCO data and the health system’s reporting capability. This could begin with an in-depth conversation with MCOs about data sharing and a pay-for-reporting APM.

APM Design

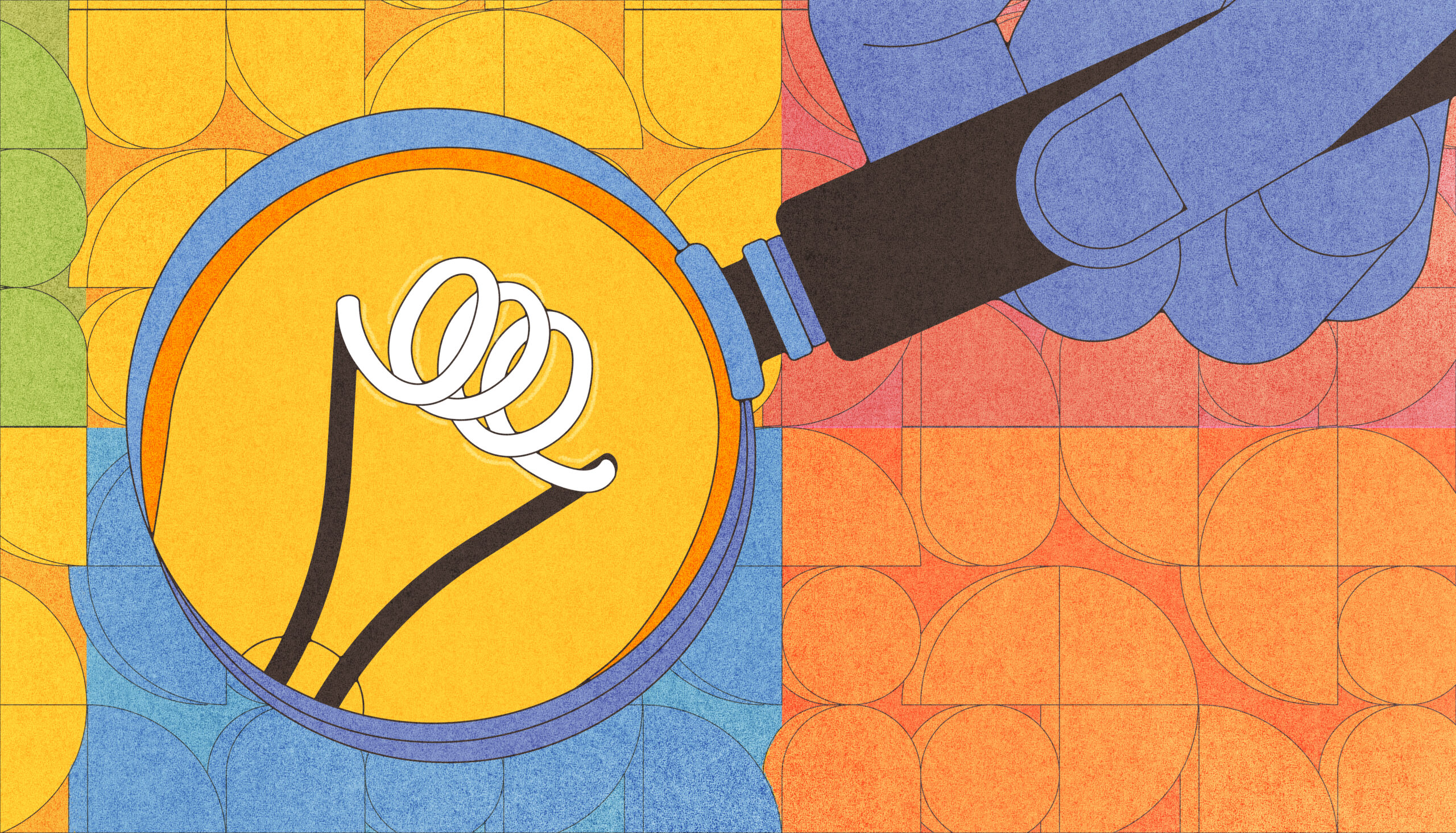

In conversations around the HCP LAN Framework, the health systems indicated they preferred to start with Category 2 (refer to image below) – foundational payments for infrastructure and operations and pay for reporting. It is important to note that the various levels within the APM framework purposefully allow providers and payors to implement these models slowly to ensure greater success and support providers as they advance along the continuum of APMs. Given MCOs’ need for more timely information about their members, pay for reporting may be a good starting place for building necessary infrastructure and trust to make the model sustainable long-term and support future more advanced APMs.

Fee for service — no link to quality & value

CATEGORY 2

Fee for service — link to quality & value

(A) Foundational Payments for Infrastructure & Operations (e.g., care coordination fees and payments for HIT investments)

(B) Pay for Reporting (e.g., bonuses for reporting data or penalties for not reporting data)

(C) Pay for Performance (e.g., bonuses for quality performance)

CATEGORY 3

APMs built on fee-for-service architecture

(A) APMs with Shared Savings (e.g., shared savings with upside risk only)

(B) APMs with Shared Savings and Downside Risk (e.g., episode-based payments for procedures and comprehensive payments with upside and downside risk)

*Risk-based Payments NOT Linked to Quality

CATEGORY 4

Population-based payment

(A) Condition-Specific Population-Based Payment (e.g., per member, per month payments, payments for speciality services, such as oncology or mental health)

(B) Comprehensive Population-Based Payment (e.g., global budgets or full/percent of premium payments)

(C) Integrated Finance & Delivery System (e.g., global budgets or full/percent of premium payments in integrated systems)

*Capitated Payments NOT Linked to Quality

Contracted Entities

Initial conversations included the idea for a 3-way contract between the bridge, a provider, and an MCO. APMs are already difficult to design and implement, so a 3-way contract may not be the most feasible approach. An APM contract between a health system and the MCO is more desirable, and a health system must decide if it can reimburse the bridge to continue to assist with the infrastructure or if it (and/or the MCO) needs to build internal infrastructure.

Population

The three health systems serve different populations and have a different payor mix. They each expressed interest in focusing on pregnant women, a good place to start for a more focused and structured approach that aligns with HHSC’s and MCOs’ interests in improving maternal health outcomes.

Several new requirements lay the groundwork for AHC. Hospitals will need to develop infrastructure and workflows to comply, and compliance is associated with reimbursement and incentives increasing the likelihood that the health systems will implement infrastructure necessary to implement the model and APMs. These requirements include:

- The new CMS rule requiring special needs Medicare Advantage plans to use health risk assessment tools that include questions about certain social needs (housing stability, food security, and access to transportation);

- CMS reporting requirement for social drivers of health for hospitals that will be voluntary in 2023 and mandatory in 2024, with a payment determination to be in place by 2026;

- Two new CMS measures — the Screening for Social Drivers of Health and the Screen Positive Rate for Social Drivers of Health — that seek the percentage of adult patients who are screened for housing instability, transportation needs, utility difficulties, and interpersonal safety upon admission to a hospital; and

- HHSC requirement for hospitals to report on quality measures to receive enhanced payments under the hospital directed payment program (The Comprehensive Hospital Increase Reimbursement Program [CHIRP]).

Another question that exists is how will eligibility be determined if a Medicaid APM is developed with a specific payor – for example, will a site only screen a specific payor’s members, or will a site be expected to screen all eligible entities but only be reimbursed for that payor’s members? Based on discussion, we recommend that the site initially screen all patients and then reconcile attribution with health plans on a reoccurring basis to tie payment to Medicaid members.

Navigation and Referral

Given the fact that the staffing may not still be available at the sites since the grant has ended, it may not be feasible for a future APM to include the health system providing the navigation services, rather focusing on screening, data sharing with the MCO, and providing an initial referral or handoff back to the MCO.

Recommendation and Future Opportunities

Start Small: Pilot an APM

BCBS Minnesota implemented an APM to sustain the AHC model and recommended other entitles start small with discreet and measurable interventions with targeted populations to build evidence, build trust, and make the case to expand efforts.

A next step could be to identify a health system and an MCO willing to work together to pilot the model on a smaller scale. For example, focusing on one or two hospital labor and delivery departments for one health system and focusing on the pregnant women population. An APM with an individual health system and a single MCO that is thoughtful and successful could potentially be replicated across payors and sites.

Leverage Medicare

Given the new policies adopted in Medicare, there may be a greater possibility to engage STAR+PLUS plans once the contract goes live in September 2024.

Conclusion

The AHC model is a proven model with goals and outcomes that align with MCO contract requirements and goals. Recent policy changes and programs in Medicare and in the Medicaid program around non-medical drivers of health may create the necessary infrastructure, incentives, and opportunities to engage in APMs to implement and sustain the AHC model in the future.

Acronym Glossary

AHC Accountable Health Communities

APM Alternative Payment Model

CBO Community-Based Organization

CMS Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services

GH Greater Houston Area

HRSN Health-Related Social Need

MCO Managed Care Organization

NMDOH Non-Medical Drivers of Health

More from Digging Deeper

Rooted in Community: A Journey to Transform our Food System with Sustainable Food Center

The Sustainable Food Center took a team approach to applying it to their work—pulling in staff from community engagement, policy, food access, and evaluation. Their resulting report provides a comprehensive look at the practical and emotional choices and navigation points that people experience in meeting basic food needs.

Learning with Communities as they Discover Solutions for Nutrition Security

Aetna and EHF joined forces to explore food security using the Positive Deviance Approach, which uses solution discovery to address complex social challenges. Instead of asking, “Where is food insecurity the worst and how do we fix it?”, solution discovery asks, “Are there people who consistently have healthy food even

Finer Points and Nuances of The Positive Deviance Approach

The foundation of the Positive Deviance approach is the belief that in every community, organization, or social system, there exist individuals or groups whose uncommon behaviors and practices have enabled them to succeed (relative to their peers) while facing the highest odds and with no extra resources. These individuals deviate