In 2021 and 2022, Aetna and Episcopal Health Foundation (EHF) collaborated to learn more about food security, centering on the everyday challenges people face while trying to meet their food needs. Departing from conventional methods, this partnership embraced a solution-oriented perspective. This Digging Deeper post is part of a blog series exploring this journey from different viewpoints.

What is the premise of the Positive Deviance Approach?

The foundation of the Positive Deviance approach is the belief that in every community, organization, or social system, there exist individuals or groups whose uncommon behaviors and practices have enabled them to succeed (relative to their peers) while facing the highest odds and with no extra resources. These individuals deviate from the norm (hence “deviance”) and have succeeded in overcoming the problem (hence “positive”). Because these individuals found success in spite of great odds represents social proof that local and sustainable solutions exist, and we may be able to learn from them.

PD has its origins in the early 1990s effort to combat childhood malnutrition among impoverished villages in Vietnam. Working with Save the Children, the husband and wife team of Jerry and Monique Sternin discovered that 64 percent of poor children in four Vietnamese villages selected for intervention were malnourished. Instead of focusing on what was going wrong with those malnourished children, the Sternins wondered what the families of the poor, yet well-fed children were doing right. These poor families, who had no special resources but managed to avoid malnutrition, represented Positive Deviants.

Community members found that the PD families were engaging in simple behaviors: adding tiny protein-rich shrimp and crabs from paddy fields and greens of sweet potato plants to meals; actively feeding children so no food was wasted; and breaking up the two-meal-a-day norm into four or five smaller meals. Interestingly, these simple behaviors of these families were uncommon and hidden from public view and, remarkably, the practice of these behaviors did not require any additional resources, meaning they were accessible to all.

Armed with this information, and defying the conventional practice of now “telling” others what to do, the Sternins developed a two-week nutrition program focused on “doing.” The families of malnourished children were asked to forage for shrimp and crabs and sweet potato greens. They were encouraged to actively feed their children and more often. Malnutrition decreased by 85 percent in the four villages where the PD approach was piloted, and the approach over time was scaled regionally and nationally with outstanding results.

A search for uncommon, replicable, and validated PD behaviors

A critical step of this approach is to identify PD behaviors in a community by harvesting data: Who in the community is at the highest risk for a given problem (faces the heaviest odds) but yet has succeeded? For example, in Vietnam’s classic study, the guiding question was: Are there children under the age of five who hail from poor families in rural areas and were well nourished? In the context of food security work in central Texas, for example, a general question could be: Are there families in Travis County who are large (more than 3, 4, or 5 children), socio-economically poor, in a food desert, and who are food secure?

If the answer is yes, then the inquiry turns to focus on discovering what these families are doing that others are not: uncommon behaviors and practices. As noted previously, in Vietnam, the uncommon practices included mothers adding shrimp, crabs and sweet potato plant greens to their pho. While these resources were accessible to all, the shrimp and crabs from rice fields were looked upon as being food for ducks and chickens, and not for children. By being accessible to all, these practices were replicable.

Who decides a certain behavior is uncommon? Researchers from the “outside”, despite their rigor and best intentions, are usually not be the best people to determine that.

In a PD inquiry, one is not looking for the identified behaviors to be common across successful individuals. A single validated positive deviant behavior, e. g., adding protein—shrimp and crabs—to a child’s diet, or micronutrients through plant greens is by itself valuable. No thematic saturation is needed, as is common in qualitative research.

While the above sounds simple enough, it is not. Who decides a certain behavior is uncommon? Researchers from the “outside”, despite their rigor and best intentions, are usually not be the best people to determine that. In Vietnam, once the community members identified the presence of PD, they are the ones who went to look for what the successful families were doing that was uncommon. Only members of the same community could know that adding shrimp and crab was uncommon. PD involves working closely with affected community members so they can themselves identify and implement the effective strategies of their peers.

Professor Arvind Singhal, Ph.D., is the Samuel Shirley and Edna Holt Marston Endowed Professor of Communication and Director of the Social Justice Initiative at The University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP). He has been a student and practitioner of the Positive Deviance (PD) approach since 2004, when he met Jerry and Monique Sternin, pioneers of this approach. Arvind teaches the only full-length semester long course on PD and has helped establish PD learning networks in the U.S., Netherlands, Norway, U.K., Sweden, Japan, Israel, Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda, and India. Author of three books, dozens of case studies and 30 peer-reviewed essays, Arvind served as technical advisor and enthusiastic supporter to the sites and funders.

More from Digging Deeper

Texas’ Medicaid Managed Care Learning Collaborative: Origin, Contexts, and Key Takeaways from 2024 Efforts

Episcopal Health Foundation (EHF) launched a partnership with key stakeholders more than six years ago to harness the capacity of MCOs in addressing non-medical needs of Medicaid members. The Learning Collaborative’s work has contributed to key legislation and policy changes that advance the NMDOH work of Medicaid MCOs to continually

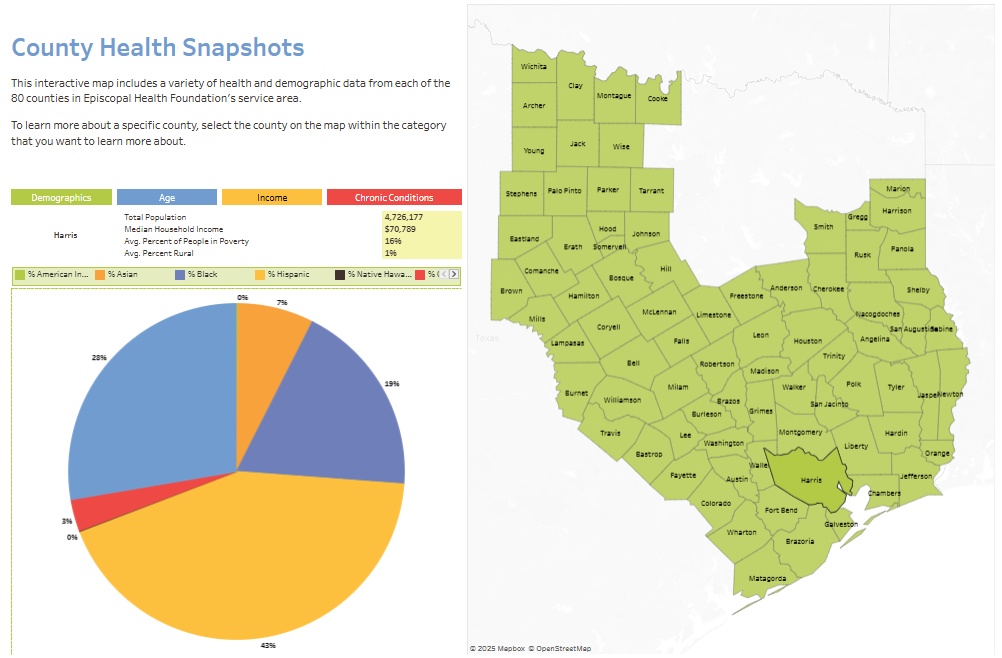

Understanding Community Health Through Data Mapping

EHF’s research team has released an updated and improved County Health Snapshots data mapping tool. EHF’s County Health Snapshots (CHS) tool provides a peek into the important demographic factors and health outcomes within the EDOT.

Key Takeaways from EHF’s Policy and Research Reports in 2024

As a major health philanthropy in Texas, EHF has developed a diverse range of tools, both financial and non-financial, that help to improve the health of all Texans.